Soccer in the Streets Scores Big with Five Points Station

Thanks to the first grant awarded by the Atlanta United Foundation, Soccer in the Streets is scoring big with their transit meets ‘fútbol fusion.’ Executive Director, Phil Hill, kicked us over some knowledge on their goals and what’s next for Atlanta’s soccer revolution.

What do Akon, the Five Points MARTA station, and social equity all have in common? If your answer was ‘soccer,’ you are on the ball! Bringing the world’s most popular sport to Atlanta’s Five Points MARTA Station, Soccer in the Streets is changing the lives of children one goal at a time.

Thanks to the first grant awarded by the Atlanta United Foundation, Soccer in the Streets is scoring big with their transit meets ‘fútbol fusion.’ Executive Director, Phil Hill, kicked us over some knowledge on their goals and what’s next for Atlanta’s soccer revolution.

Tell us about Soccer in the Streets.

In 1989, Carolyn Mackenzie found out that soccer was a great way of guiding the youth of Jonesborough towards a positive lifestyle – or at least keeping them out of trouble. That mentality continues today, but we have greatly expanded even adding a life skills curriculum. During the initial stage of engagement, we host activation events in various communities or parks to get kids involved in soccer. The next level of our programming is a more organized form of play run through schools and community centers. From there, we create organized leagues and get the parents involved through coaching. Anyone can go out and get 5,000 kids to play soccer in a one-time festival, the hard part is keeping them on the field and giving them the opportunity to play continuously. It is even more challenging to then get those kids engaged in healthy lifestyle choices; however, that is precisely what we do.

I have been involved with Soccer In The Streets since 1998 as volunteer and Board Chair. Last May I took over the Executive Director role because I was excited about the big changes happening in soccer across Atlanta.

How is Soccer in the Streets changing with Atlanta?

Many things have changed in Atlanta which impacts what we are able to do. For example, the new Major League Soccer team, Atlanta United FC, is in town and the tide of soccer is rising with that. Soccer’s profile is rising across the board but most excitingly it’s going into communities where soccer has not been traditionally offered. Kids in African American neighborhoods are asking to play in big numbers and this was less the case five years ago. Funny enough, awareness of the sport has come in part due to things like Xbox FIFA and music stars who attach themselves to soccer because it’s cool. A lot of people make sweeping assumptions about soccer; they know Latino and refugee communities want it and think that African Americans don’t – which is just not true. It’s like African American communities are saying, ‘why do you think we don’t want you here? We do!’

The head injury issue with American football also comes up a lot. We hear it from schools and parents that they want a new alternative sport for their kids.

There is also greater attention being paid to girls in sports and providing them with constructive activities. One of the community centers we work with, Dunbar Community Center in Pittsburg, had virtually no girls in sports programs because they just offered basketball and football. They wanted something that would attract girls, which is a perfect fit for us since our programs are evenly split between boys and girls.

Tell us about your program with MARTA, Station Soccer.

One of the Soccer In The Streets board members had this idea to put soccer fields at MARTA. The very progressive management team at MARTA went along with it and we opened the world’s first soccer field in a train station. MARTA likes the idea of building community and green spaces around their stations; soccer was a great fit. We now have one field at Five Points which was funded by the Atlanta United Foundation and it’s going great.

We have found that transportation is the single biggest issue for low-income families interested in playing organized sports. Unless they can walk, they can’t get involved; soccer in America generally caters to middle and upper class kids with a pay-for-play model and a reliance on consistent transportation. Having soccer at MARTA unties the knot for one of the biggest obstacles families face and we look forward to continuing to remove that barrier.

The idea is not to build just one soccer field but to do this at 10 different MARTA stations. Our goal is to build green spaces at stations and to use it as a community hub for activities. Besides Five Points, the stations that will have soccer fields are all very residential. We want to use those stations to connect communities to a network of healthy living across the city while taking advantage of public transportation. This project has really grown a life of its own. People are drawn to the green space at Five Points and we are looking forward to seeing how people get engaged as we expand to new communities. We are looking forward to seeing how placing healthy lifestyles around transit impacts people all over the city.

How can readers support Soccer in the Streets?

One initiative we are very excited about is running paid adult leagues on our fields. It helps to diversify our funding so we have consistency of service for our kids – and it’s also a lot of fun. All of the proceeds from those leagues go to fund our programming in the community around the field. We just launched four organized leagues and pick-up sessions at Five Points; we even have a lunchtime league for restaurant workers and are kicking off a league in which City of Atlanta departments play each other. We have had an incredible response to these leagues, so if you want to help us, come and be part of it. We have more information on our Station Soccer site. Come and join in!

We also host four fundraising soccer events throughout the year. Anyone can sign up to be on a team and then raise money to play in the game. It’s a very successful, engaging way for people to get involved in what we do. We are taking applications for our first corporate event, in which corporations can apply to participate in a tournament with employee team. Playing with us is a great way for people to enjoy soccer and do good at the same time.

*Published by 'Gather Good ATL' http://gathergoodatl.com/soccer-in-the-streets-scores-big-with-five-points-station/

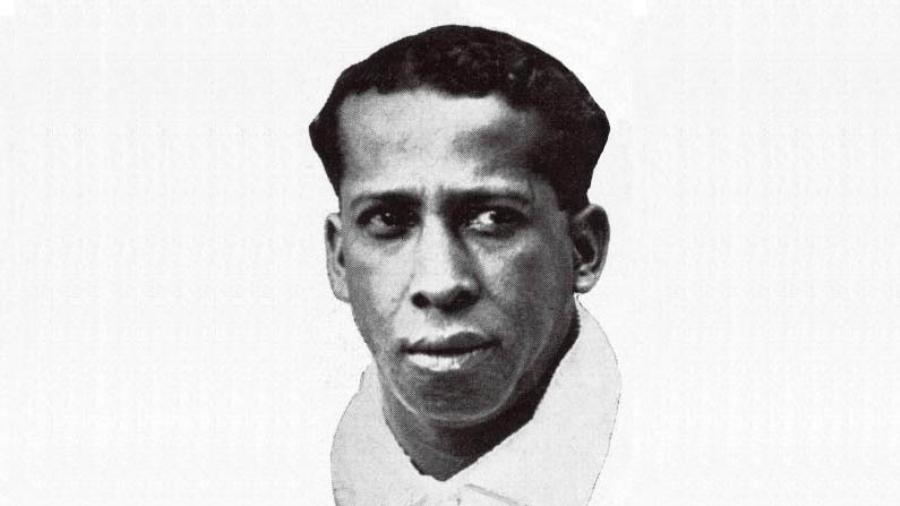

The Myth and Magic of Jose Leandro Andrade, Soccer's First Black Icon

At times, the story of Jose Leandro Andrade sounds semi-fictional, and there is a good chance that aspects of it are. Far from diminishing his incredible legacy, however, the uncertainty over what did and did not take place serves to strengthen the intrigue surrounding one of football's first truly global stars.

At times, the story of Jose Leandro Andrade sounds semi-fictional, and there is a good chance that aspects of it are. Far from diminishing his incredible legacy, however, the uncertainty over what did and did not take place serves to strengthen the intrigue surrounding one of football's first truly global stars.

The son of a former slave, Andrade was born in Salto, a city in north-west Uruguay that would later produce Luis Suarez and Edison Cavani. Though he grew up in poverty, Andrade's incredible footballing ability transformed him into an international celebrity, complete with all the trappings of fame.

Today, Andrade is a relative unknown in the English-speaking world. Scan through a few lists claiming to chronicle the greatest footballers of all time, and in some cases his name is absent altogether. Yet this was a man who earned three world titles with his country, can correctly be called football's first black icon, and who was once among the most famous sportsmen on the planet.

The mystery and myth that surround Andrade stretch back to his arrival in this world. It is widely recorded that his father, a former slave named José Ignacio Andrade, was 98 years old at the time of his birth. It has also been written that the elder Andrade possessed magical powers, which seems about the only explanation for a man of his vintage fathering a child, or indeed living to such an age in turn-of-the-century Uruguay. As a teenager, Andrade Jr. lived in Montevideo and worked as a carnival musician, a bootblack, and – according to popular legend – as a gigolo. At least one of those skills would serve him well when he became the toast of inter-war Paris.

A brilliant footballer from a young age, he began his playing career at Montevideo side Bella Vista. Andrade first appeared for the national team in 1923, and was part of the squad which won that year's South American Championship (now the Copa America). This secured Uruguay a place in Paris for the summer of 1924, where they would be their continent's representatives at the Olympic Games. Here they would take on the best sides that Europe had to offer – 18 in total – with the United States, Turkey and Egypt completing a very Eurocentric entry list.

Andrade's ethnicity was noteworthy at the 1924 Games, and his place in the squad made him the first black international footballer to play the sport at Olympic level. That said, he was not a first for La Celeste: Uruguay had fielded black players for several years, a progressive policy that had drawn the ire of their continental rivals in the early 20th century (Chile went so far as to call it cheating, only backing down when Uruguay threatened to make it a diplomatic matter).

In Football in Sun and Shadow, the late Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano described the 1924 squad as "workers and wanderers who got nothing from football but the pleasure of playing." Along with the shoeshiner and carnival performer Andrade, their number included a meat packer, a marble cutter, and an ice salesman.

Despite being South American champions, Uruguay did not travel to Europe in style, instead sailing in third-class accommodation. Ahead of the Games they travelled in second-class carriages, slept on wooden benches, and undertook a tour of Spain to pay for their meals.

The Europeans gave them little chance, though their initial opponents, Yugoslavia, did pay them one backhanded compliment. Ahead of the opening-round game, the Yugoslavs are said to have sent spies along to watch the Uruguayan players train. They left with reports of misplaced passes and a poor eye for goal. A few days later, Uruguay routed them 7-0. They had been aware of the Yugoslav spies and purposely trained poorly to throw their opponents off the scent. Then as now, Uruguayan football was bolstered by a healthy dose of cunning.

The Uruguay players at the 1924 Games. Andrade stands back from his teammates, second from left // PA Images

Perhaps they were also spurred on by the lack of respect they were shown before the match started, when their flag was hung the wrong way up and a Brazilian march was played instead of their national anthem. Affronted or not, Uruguay were a vastly superior side.

Next they beat the United States, who escaped with a comparatively respectful 3-0 defeat. In the quarter-final they played hosts France in front of 30,000 supporters at the Stade Olympique, where Uruguay ran out 5-1 winners. By now, Europe was certainly taking notice.

The semi-final was their sternest test – they required an 81st-minute penalty to beat an excellent Dutch side 2-1 – before a comfortable 3-0 win over Switzerland in the final secured the gold medal. Gushing praise ensued: the editor of France's L'Equipe described the Uruguayans as being "like thoroughbreds next to farm horses". The newspaper added that they possessed "a marvellous virtuosity in receiving the ball, controlling it and using it." The limited footage of their players in action shows the Uruguayans to be a considerable distance ahead of their rivals, always moving, always finding space, against a predominantly stationary opposition.

Andrade did not get among the goalscorers in Paris that summer, with Pedro Petrone (seven) and Héctor Scarone (five) providing the bulk of their firepower.

Yet it was Andrade who stood out as the star performer for La Celeste. Though just 22 at the time, he orchestrated play with a cool head that belied his years. He was physically strong, but played with elegance in the half-back position, performing a role comparable with the modern holding midfielder. Richard Hofmann, a German international who appeared at the 1928 Games, called Andrade: "A football artist who could simply do anything with the ball...a tall guy with elastic movements, who always preferred the direct, elegant game without physical contact and was always ahead with his thoughts by several moves." Contemporary comparisons have been made with Zinedine Zidane, a player who is regularly found among the top-10 of those 'greatest of all time' lists. During the 1924 Games, the French dubbed Andrade La Merveille Noire – the Black Marvel.

As one might expect, Andrade enjoyed his new-found fame in Paris. He regularly disappeared from the team hotel and, when a teammate was sent out to find him, it was reported that the star player was "in a luxury apartment in one of the most exclusive areas of the city, surrounded by beautiful women, like a sultan in his harem." He caught the eye of the celebrated author and journalist Colette – she called the Uruguayans "a strange combination of civilisation and barbarism...better than the best gigolo" – and he danced with Josephine Baker, who as the first black woman to star in a major motion picture was something of a kindred spirit.

But this indulgence in his new status came at a cost. For Andrade's homecoming, the local black community in Montevideo arranged a welcome party in his honour. He did not attend. It is quite possible that he possessed this kind of arrogance long before finding fame, of course, just as it is possible that dancing with a burgeoning movie starlet changed him.

In 1924 Andrade joined Nacional, winning Uruguay's Primera Division the same year. He would remain at the club until 1931, albeit without adding another domestic title, before becoming champion twice more with Penarol, for whom he played between 1931 and '35.

Andrade (back row, second from left) with his Nacional teammates in 1925 // PA Images

Yet that seems largely insignificant given the international successes he would add to the 1924 gold medal. Four years later, at the Amsterdam Games, Uruguay retained their Olympic title. Andrade was now less influential as a player (he had reportedly contracted syphilis by this stage), but even more of a star attraction, with huge crowds turning out to see La Merveille Noire. Uruguay defeated the hosts (2-0), Germany (4-1), and Italy (3-2) to set up a final against their fierce continental rivals Argentina.

The superiority of South American football was confirmed by a 1-1 draw, making Argentina the only side in nine Olympic matches to hold Uruguay over 90 minutes. The replay was tight too, but the holders retained their gold medal with a 2-1 victory.

Two years later Uruguay hosted the inaugural World Cup. Despite his dwindling influence Andrade remained part of a team that won their group and destroyed Yugoslavia 6-1 in the semi-finals to set up another deciding match with Argentina. A 4-2 win at the Estadio Centenario in Montevideo saw La Celeste crowned champions. Andrade had yet another medal to add to his collection.

With the 1924 and '28 Olympics officially recognized by FIFA as world championships, Uruguay could now lay claim to a hat-trick of world titles, and today wear four stars above their badge (the fourth for their 1950 World Cup triumph). Andrade, along with three of his long-time teammates, has a trio of world titles to his name; only Pele can match their haul.

But while the great Brazilian has lived long into retirement, Andrade's post-football life is a sorry tale. He would eventually lose the sight in one eye, though whether this was caused by a collision with a goalpost or the syphilis is unclear; it is possible that the former was exacerbated by the latter.

Either way, it contributed to his downfall. He was in attendance at the 1950 tournament, when his nephew was among the players who won Uruguay's second World Cup, but as the fifties progressed he slipped deeper into alcoholism and ill health. In 1956 a German journalist, the aptly named Fritz Hack, sought Andrade out in Montevideo. "What I found was horrible", Hack later said, reporting that Andrade was holed up in a dirty basement. "In a spartanly furnished room I found Andrade, a total alcoholic and blind in one eye, a consequence of the injury. He could no longer follow my questions, which were answered by his beautiful wife, the sister of one of the former Olympic champions."

One year later Andrade was dead. He owned almost nothing, though some of the medals he won as a globally renowned footballer remained in a shoebox. It is tempting to think that amid the little he had left were a pair of Olympic golds and a winner's medal from the inaugural World Cup.

But we do not know for certain. Like so much of Andrade's life, we are given enough information to formulate ideas, then left to decide for ourselves what might be true.

More than half a century on from his death, Andrade remains a hugely relevant figure. At a time when ideas of white racial supremacy were rife across Europe, he was the Paris Games' star player. What's more, he had the courage to ignore white notions about how a black man should behave, treating Paris as his own personal and professional playground. In this respect, there are parallels to be drawn with boxers Jack Johnson and Muhammad Ali. Yet his importance is not limited to race: academic Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht believes Andrade was "responsible more than anybody else in the first third of the 20th century for putting football on the map of international sports."

Despite his former fame, Andrade's life now seems somewhat obscured, shrouded in myth and mystery. All that feels entirely real is the football, though even this is an incomplete body of work, with only brief and fuzzy glimpses of his genius on the pitch surviving.

A sense of mystery was important in 1924, when Uruguay arrived in Europe as complete unknowns. The players were simply names on a sheet of paper and their incredible ability thus had the capacity to shock those who saw it in the flesh. Andrade exemplified this perhaps better than anyone else.

His footballing ability quickly became evident that summer, yet much remains unclear. The stories of what he got up to off the pitch and the manner in which he lived his final years are still open to interpretation. Did he have an affair with Baker when they met in Paris? What drove him to such self-destructive drinking? It is more interesting not to know. The uncertainty around Andrade allows us to fill in the gaps ourselves, to believe some of the more outlandish stories and fit them to our own understanding of the world.

The Interns' Corner

I am Nicolas Mejia, a student from Cristo Rey Atlanta Jesuit High School, and an intern for Soccer in the Streets. Soccer in the Streets is a local Atlanta organization that uses soccer to help teens, within the Atlanta community, who are refugees due to social issues in their home countries. Our motto is “Play. Grow. Work. Succeed.”

Phil Hill (left) with Nicolas Mejia (right) setting up the goals at 'Station Soccer'

I am Nicolas Mejia, a student from Cristo Rey Atlanta Jesuit High School, and an intern for Soccer in the Streets. Soccer in the Streets is a local Atlanta organization that uses soccer to help teens, within the Atlanta community, who are refugees due to social issues in their home countries. Our motto is “Play. Grow. Work. Succeed.” which really represents what we want our youth to enforce when they go out and live their day-to-day life. As for the experience of our youth, we wish to give a positive environment where everyone can be comfortable on the field. The same goes for the office, as we strive to always achieve a friendly environment. In the office, you are always part of the group. We have grown trust with one another that allows the whole team to work in a peaceful environment.

In my experience working at Soccer in the Streets, I have really enjoyed the environment here and I feel fit to perform the tasks I am given, which involve my strongest skills. When I come in every day, I have a daily plan set up so that I am occupied while my other co-workers arrive. Once my supervisor arrives, she is ready to tell me what we will do the rest of the day and we get right on it. I am almost always working on the computer, which actually fits me well as I am very tech savvy. I help set up the calendar on a program we use called Upshot and create documents. As I help in the office, I also feel like I help on the tasks we have outside of the office. I set up boxes that will be sent out to project sites, or I may even set up banners for an event, or at times, I create sign-up sheets for a pick-up event.

On some special occasions we go out of the office to other places for a project. One of my favorite projects has been the creation of the soccer nets at our most recent project called, Station Soccer; the first soccer station built within a station. Initially, we had to carry the posts of the goals to the field. Each one was sizable and heavy so we had to make two trips from the shoppe to the field. Once we transported the goals to the field, we had to install the netting with metal chains. I had the pleasure of finishing installing one of the nets and take a few shots in order to see their durability. Another trip that we made was around the street near the office. I managed to see the new building for my school, enter Ebenezer Baptist Church which was one of Martin Luther King’s local churches, and I even had the chance to see a statue of Gandhi which lies directly in front of a pathway of feet that were imprinted by peaceful leaders.

On many occasions we also host special meetings or projects in the office. A while back, around the time I began working here, the office had just recently relocated and needed some organizing; I was responsible of organizing and labeling one of our major closets. It took a while to find a way to organize it, but eventually I managed to set it up to where all you had to do was locate the item you were looking for on a list and it would lead you directly to a section. Another task I was responsible for was copying notes from the board and then formatting them the same way they were on the board. I had to color code certain notes and make comments on the side as they were on the board. In the end I learned something new about Google Docs’ formatting, which I eventually used for a project in my World History class.

Out of work, I have also tried to contribute to Soccer in the Streets. I came to the inauguration for Station Soccer where I was able to meet with Tony, who is currently the Atlanta United Academy Director, and see whether he had space for a player on the team. The team was already full, but luckily they have tryouts in August and he invited me to come and show my potential. Another event I went to was the Cristo Rey Atlanta Jesuit High School collaboration with Soccer in the Streets at Station Soccer where they filmed us playing and testing out the new field. Also, a huge event that I collaborated on, both in the office and on the field, was the first pick-up match at Station Soccer. I helped create the sign-up sheet and I got to play the entire day, so it was a win-win situation.

Honestly, being chosen to work at Soccer in the Streets was the most unexpected event in my life. I knew that when my Corporate Work Study Manager talked to me about this job she had heard my opinion of it and that I would love to see what it was about. However, I had no idea she had actually chosen me to have the privilege of working here. Even my companions at the school were amazed by how lucky I was for getting the chance to come and work here. I am thankful that I was chosen because coming to work here has opened me up to a whole new variety of careers; careers that my previous job did not, and that add onto my list for my future.

Nicolas Mejia

Student, Class of 2019

Cristo Rey Atlanta Jesuit High School